Please check our FAQs section if you unsure how to use the website or looking for something specific

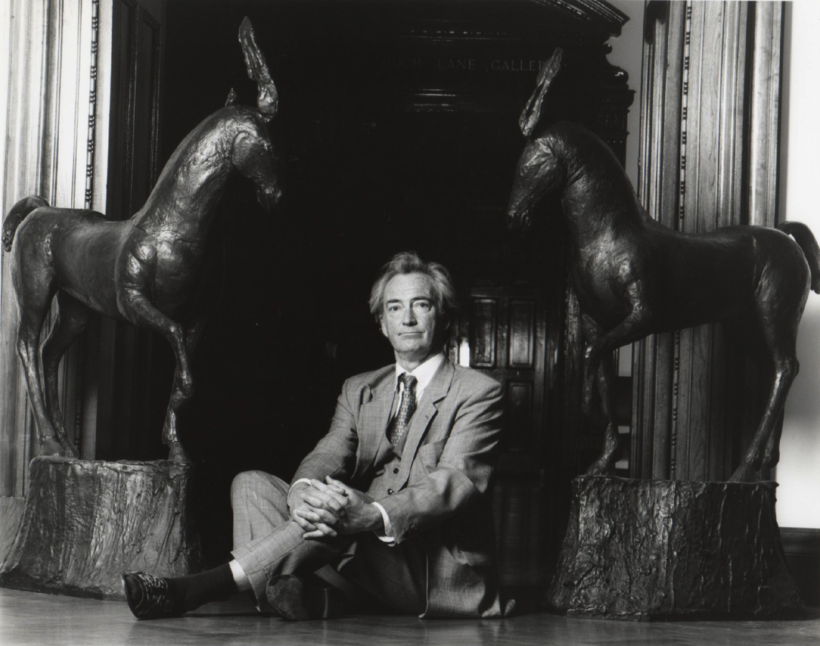

Barry Flanagan was born in Prestatyn, North Wales. He studied architecture at Birmingham College of Art and Crafts and after spells at different colleges was accepted on the Vocational Diploma in Sculpture at St. Martin’s School of Art in London in 1964. Flanagan graduated in 1966 and taught at St. Martin’s School of Art and the Central School of Arts and Crafts, between 1967 and 1971. In 1991 he was elected to the Royal Academy and he also received an OBE.

From the outset Flanagan’s work has been perceived as radical and independent. He revolutionised sculptural material when in 1965, while still a student, he showed the soft sculpture aaing j gni aa, 1965 at Better Books on Charing Cross Road in London (bought by the Tate Gallery in 1969). Works such as this and 4 casb 2 ’67, 1967 changed ideas about the language of sculpture forever. Flanagan was interested in ‘pataphysics, Alfred Jarry’s ‘science of imaginary solutions’ and this ethos is evident in the playfulness of his approach, which allows materials to find their own sculptural form, whether sand, or rope, stone, sheet metal, cloth, clay or bronze.

He was included in the exhibition, Between Poetry and Painting at the ICA also in 1965 when he contributed a finger poem, this was one of many examples of concrete poetry in the exhibition. His first solo exhibition was held at the Rowan Gallery, London in 1966. Thereafter he exhibited in numerous solo and group exhibitions, in Britain and abroad, including the seminal When Attitudes Become Form, Bern, Op Losse Schroeven, Amsterdam both in 1969 and Information New York in 1970. His first solo exhibition at Waddington Galleries, London was held in 1980.

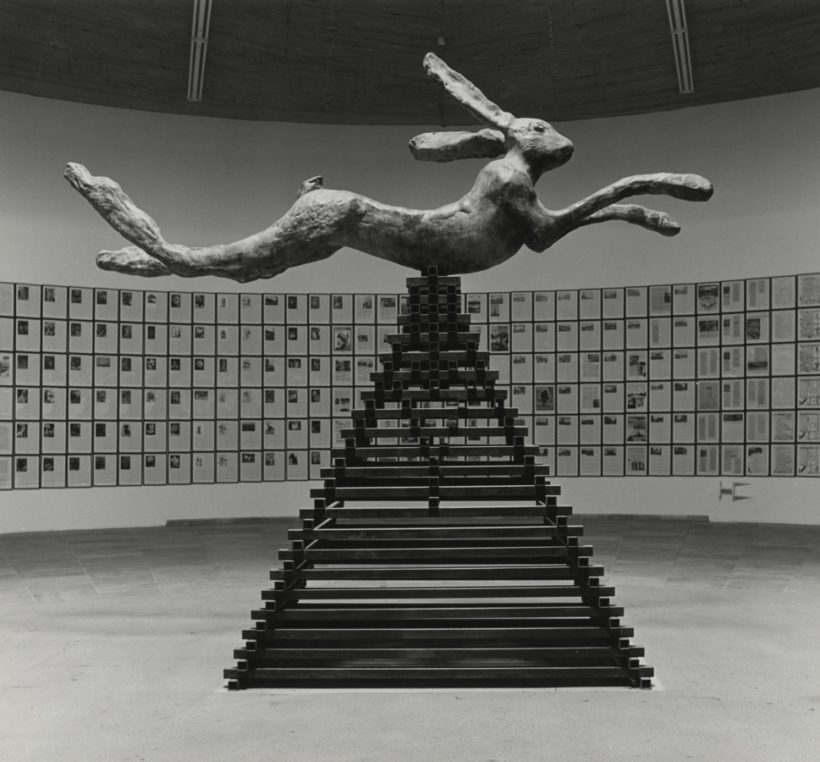

Flanagan is perhaps best known for his dynamic, often monumental, bronze hares, which spring into life and were first exhibited in the early eighties. Flanagan fuses the everyday, the imaginary and fantastical to mould clay into animal forms; hares, elephants, dogs and horses – the latter an archetype of classical sculpture. When asked about the use of the hare motif, Barry would describe the magical experience of seeing a hare running on the Sussex Downs. This event prompted the first Leaping Hare sculpture which he conceived in 1979. For the Egyptians the hare represented life. In Chinese mythology the hare is the sole inhabitant of the moon and the symbol of immortality. This mercurial image of the hare has come to stand as a surrogate for human existence and our relations to the animal world.

His return to bronze with the hare, he had previously cast work in the foundry at Central School of Art with Henry Abercrombie in 1969, was part of his exploration into different media, from the sand, rope and cloth pieces, which focused on composition and challenged previous ideas of what sculpture might constitute, to the ceramics, stone, marble and sheet metal sculptures of the seventies. Many of his works have humorous titles for example a nose in repose, 1977, which is in Tate Gallery’s collection. He was involved in happenings and dematerialised practices and collaborated with Yoko Ono in 1966 and later in 1980 with the Marjorie ‘Strider’ dance company. Like his contemporaries from St. Martin’s School of Art, Richard Long, Gilbert & George and Bruce McLean, Flanagan experimented with film. He was included in Land Art, Gerry Schum’s Video Gallery exhibition with the film, a hole in the sea 1969.

'One of Britain's most original and inventive sculptors'. Penelope Curtis, former director of Tate Britain, has described Flanagan as 'a maverick figure but a maverick who was absolutely central to the artistic conversation of the 1960s and 70s'.Artlyst, January 2016

The exhibition The horses of San Marco at the Royal Academy of Arts, London, in 1979 made a deep impression on Flanagan. Henry Abercrombie described the exhibition’s impact on Flanagan’s thinking and approach to sculpture, where the sheer tactile physicality of the ancient modeled horses created an aura and majesty. It was the ancientness of the sculptures that demonstrated man’s relation with the animal as much as the desire and means to represent it. The varied patinas and gilding also provided substantial material to investigate the properties of bronze and the catalogue included essays on ancient casting methods, gilding in the Greek and Roman eras and an investigation of the foundry techniques used to cast the horses of San Marco as well as analyses of the best ways to preserve the horses. The bronze sculptures of horses each have a distinctly different character, for instance the beautiful majestic and powerful Bronze Horse, 1983 at Jesus College, Cambridge to the gentle diffidence of Field Day 1, 1986, also known as the Korus Horse in San Eulalia, Ibiza and the mysterious, mythological qualities of Unicorn and Oak Tree, 1991.

Flanagan represented Britain at the Venice Biennale in 1982. A major retrospective of his work was held at the Fundacion ‘La Caixa’ Madrid in 1993, touring to the Musee des Beaux-Arts, Nantes in 1994. Flanagan’s bronze hares have also been exhibited in many outdoor spaces, most notably on Park Avenue in New York in 1995-6 and at Grant Park, Chicago in 1996. In 1999, he had a solo exhibition at Galerie Xavier Hufkens in Brussels followed by an exhibition at Tate, Liverpool (2000).

In 2002, a major exhibition of his work was shown at the Kunsthalle Recklinghausen, Germany, and toured to the Musee d’Art Moderne et d’Art Contemporain, Nice. In 2006, the Irish Museum of Modern Art in Dublin held a major retrospective of his work, in association with Dublin City Art Gallery The Hugh Lane, which included ten large-scale bronzes installed along O’Connell Street and in Parnell Square.

In 2011 Tate presented a major retrospective at Tate Britain Barry Flanagan Early Works 1965-1982. The exhibition surveys the early part of Flanagan’s career.

Chatsworth House holds an outdoor exhibition of fifteen bronze sculptures in 2012.

In 2014 Waddington Custot Galleries presents the first exhibition to consider the relationship between the Spanish artist Joan Miró and Barry Flanagan. It explores the inventiveness and versatility of their work and their shared interest in ’Pataphysics.

Two years later Waddington Custot presents a survey of early works in Animal, Vegetable, Mineral, curated by Dr Jo Melvin. The exhibition includes a selection of Flanagan’s key early explorations in material and form instrumental in shaping his later career, some having not been exhibited for over 30 years.

Flanagan’s little-known early light works are shown at &Model, Leeds in 2017.

Barry Flanagan was long associated with the prestigious gallery Art & Project in Amsterdam and in 2018 Kröller-Müller Museum, Netherlands exhibits works in their collection donated by Adriaan van Ravesteijn, the former gallerist.

A major survey of over sixty works by Flanagan opens at Ikon Gallery, Birmingham in 2019, filling Ikon’s two floors of gallery space entirely. In addition, monumental sculptures by Flanagan are included in Amsterdam’s Sculpture Biennial Artzuid, Sculpture Milwaukee, and Frieze Sculpture, Regents Park, London that year.

In 2021 von Bartha, Basel opens an exhibition that brings together a selection of Flanagan’s iconic bronze sculptures alongside earlier works, offering insight into the interconnectedness of aspects of his practice that are often seen as distinct.

2022 sees Flanagan’s public sculpture ‘Camdonian’, sited on the north-east corner of Lincoln’s Inn Fields since 1980, fully restored after 42 years on display.

Flanagan’s work is held in public collections worldwide including MoMA New York, Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum, Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris and Tate in London.